Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing) Sample Preparation

A comprehensive guide to preparing additive manufacturing samples for metallographic analysis, covering unique challenges, sectioning, mounting, grinding, polishing, and etching techniques for revealing build direction, layer interfaces, and process defects.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing, has revolutionized materials processing and manufacturing. However, the unique characteristics of AM materials, including porosity, layer boundaries, support structures, and anisotropic microstructures, present distinct challenges for metallographic sample preparation. This growing field requires specialized techniques to properly reveal build direction, layer interfaces, and process defects.

AM processes such as powder bed fusion (PBF), directed energy deposition (DED), and binder jetting create materials with microstructures that differ significantly from conventionally processed materials. The layer-by-layer build process results in directional solidification, thermal gradients, and potential defects that must be carefully preserved and revealed during sample preparation.

Key Consideration: Unlike conventional materials, AM samples require careful orientation planning to reveal both the build direction (Z-axis) and layer interfaces (XY plane). Multiple samples may be needed to fully characterize the microstructure.

Titanium alloy microstructure showing anisotropic grain structure, similar to what may be observed in AM materials. The directional grain growth and phase distribution are characteristic of layer-by-layer build processes. 400X magnification (DIC).

Unique Challenges with Additive Manufacturing Materials

Porosity

AM materials often contain porosity from incomplete fusion, gas entrapment, or keyhole collapse. These pores can be:

- Lack-of-fusion pores: Irregularly shaped, often at grain boundaries and layer boundaries

- Gas pores: Spherical, typically from trapped gas in powder

- Keyhole pores: Elongated, from excessive energy input

During preparation, these pores can trap abrasives, polishing compounds, or etchant, leading tocontamination and artifacts. Careful cleaning between steps is essential.

Layer Boundaries

The layer-by-layer build process creates distinct boundaries between layers. These interfaces may contain:

- Oxide films or contamination

- Microstructural differences (grain size, phase distribution)

- Residual stress concentrations

- Potential weak points for failure

Preserving these boundaries during sectioning and preparation is critical for understanding material behavior and process optimization.

Support Structures

Many AM processes require support structures that must be removed post-build. The interface between the part and support material can contain:

- Incomplete fusion zones

- Contamination from support removal processes

- Altered microstructures due to different thermal histories

- Residual stress from support removal

If analyzing support interfaces, careful sectioning to preserve these regions is essential.

Anisotropic Microstructures

The directional solidification and thermal gradients in AM create anisotropic microstructuresthat vary significantly with orientation. Grain growth, phase distribution, and defect density all depend on build direction and location relative to the build plate.

Sectioning Considerations

Sectioning AM samples requires careful planning to reveal the features of interest. The build direction and layer orientation must be considered when selecting the section plane.

Orientation Planning

Plan your sectioning to reveal the features you need to analyze:

- Build direction (Z-axis): Section perpendicular to build layers to reveal layer boundaries, columnar grain growth, and vertical porosity distribution

- Layer plane (XY plane): Section parallel to build layers to reveal in-plane microstructure, grain morphology, and horizontal defect distribution

- Oblique sections: May be useful for revealing three-dimensional relationships

Sectioning Technique

Use slow cutting speeds to minimize heat generation and preserve microstructural features:

- Cutting speed: 100-150 RPM for most AM materials

- Use thin abrasive blades (0.5-1.0 mm) to minimize kerf loss

- Apply steady, moderate pressure

- Use adequate coolant to prevent overheating

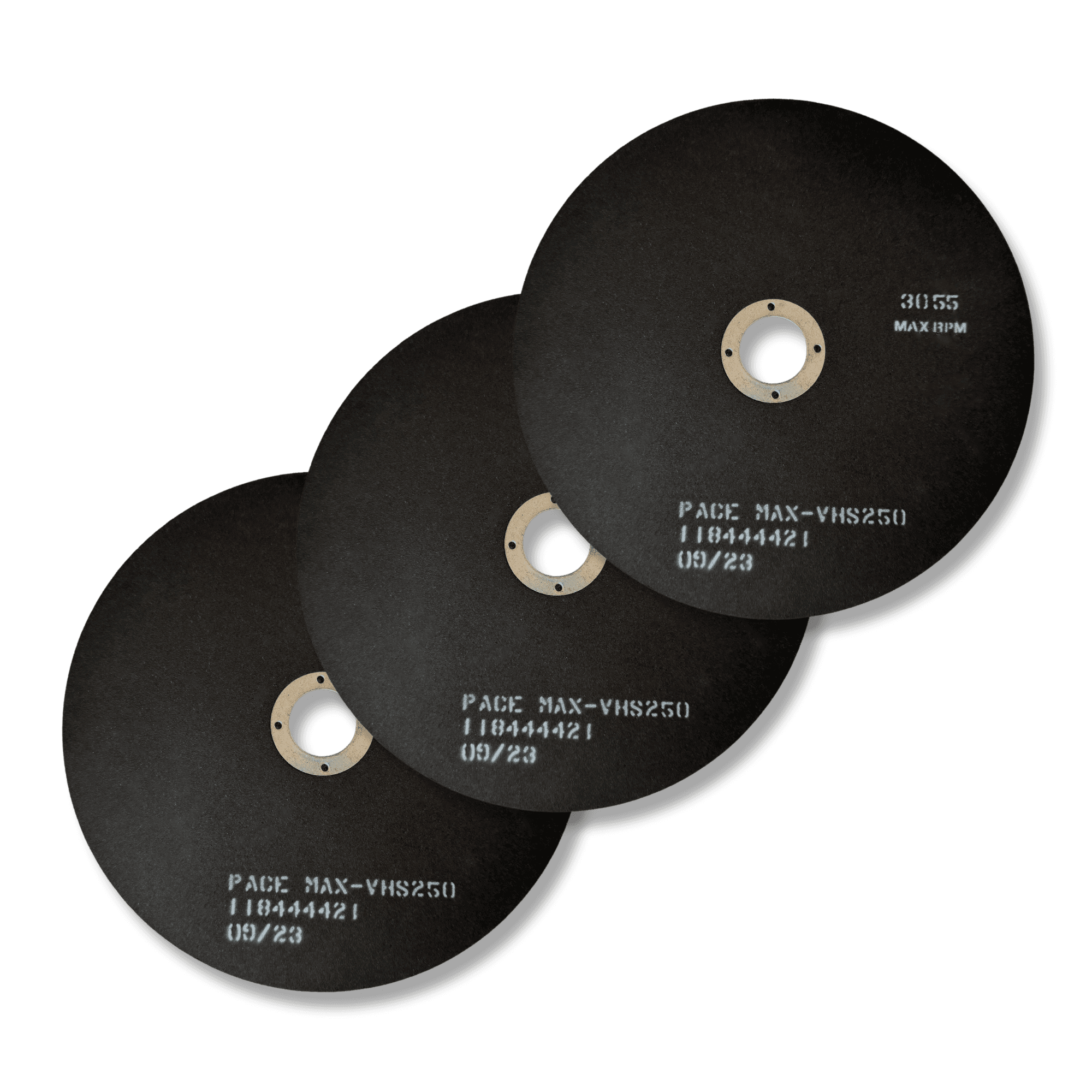

- For porous materials, consider using a slower feed rate to avoid tearing

Thin abrasive cut-off blades minimize heat generation and preserve microstructural features in AM materials. MAX-VHS or MAX-D series blades are suitable for most AM alloys.

Example Products: Abrasive Cut-Off BladesThin blades for precise sectioning of AM samples with minimal damage

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Mounting Considerations

Mounting AM samples requires special attention to preserve porosity and layer boundaries. The mounting material must not infiltrate pores or obscure features.

Compression Mounting

Compression mounting can work well for AM samples, but consider:

- Use low-viscosity mounting resins to minimize pore infiltration

- Apply moderate pressure (2000-3000 psi) to avoid collapsing pores

- Epoxy resins are generally preferred over phenolic for better edge retention

- Ensure complete curing to prevent resin shrinkage artifacts

Compression mounting presses for AM samples. Use moderate pressure to avoid collapsing pores in porous materials.

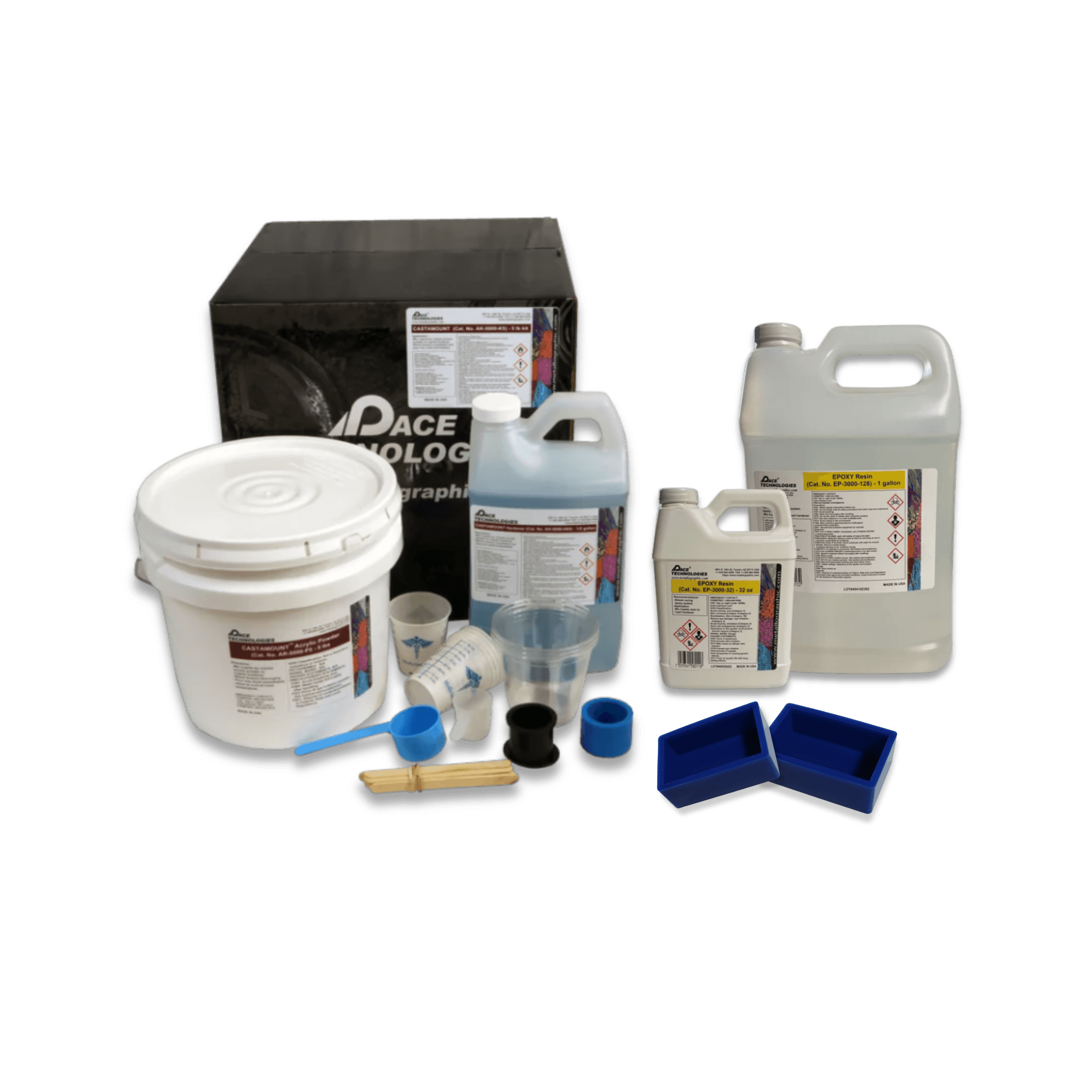

Castable Mounting

Castable mounting may be preferable for highly porous samples:

- Lower pressure reduces risk of pore collapse

- Better penetration into complex geometries

- Can use vacuum impregnation for highly porous materials

- Longer curing time but better preservation of features

Example Products: Mounting EquipmentMounting presses and castable mounting systems for AM samples

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Grinding

Grinding AM samples requires careful technique to avoid smearing, pore collapse, and loss of layer boundary definition. The presence of porosity makes these materials more susceptible to damage during grinding.

Grinding Sequence

Use a progressive grinding sequence with careful attention to pressure:

- 120 grit: Remove sectioning damage (30-60 seconds). Use light pressure to avoidsmearing porous regions

- 240 grit: Remove previous scratches (30-60 seconds). Continue with light pressure

- 400 grit: Further refinement (30-60 seconds)

- 600 grit: Final grinding step (30-60 seconds)

Special Considerations

- Light pressure: Use lighter pressure than for dense materials to avoid pore collapse and smearing

- Frequent cleaning: Clean samples thoroughly between grits to remove trapped abrasives from pores

- Rotation: Rotate sample 90° between grits, but be aware of orientation to preserve layer boundary visibility

- Water lubrication: Use adequate water to prevent overheating and remove debris

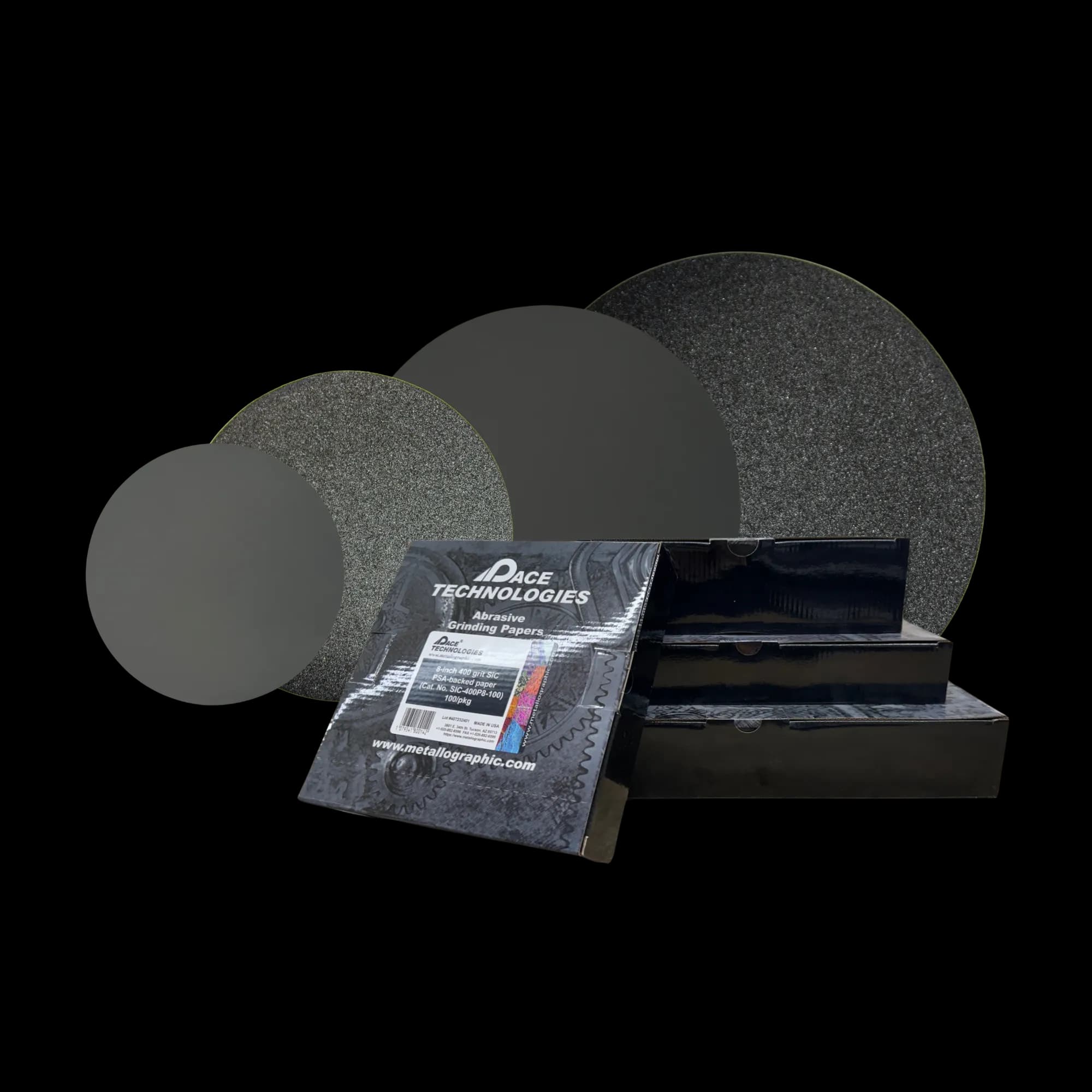

Silicon carbide (SiC) grinding papers in various grit sizes for progressive grinding. Use light pressure to avoid smearing porous regions.

Example Products: Silicon Carbide Grinding Papersappropriate SiC papers for progressive grinding of AM samples

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Polishing

Polishing AM samples requires careful technique to avoid filling pores with polishing compound and to preserve layer boundaries. The anisotropic nature of AM microstructures means that different regions may polish at different rates.

Diamond Polishing

- 9 μm diamond: 3-5 minutes on a hard cloth (e.g., Texmet). Use light pressure

- 3 μm diamond: 3-5 minutes on a medium-hard cloth. Continue with light pressure

- 1 μm diamond: 2-3 minutes on a soft cloth

Final Polishing

- 0.05 μm colloidal silica: 1-2 minutes on a soft cloth

- Rinse thoroughly with water, then alcohol

- Use ultrasonic cleaning if available to remove polishing compound from pores

- Dry with compressed air

Special Considerations

- Avoid over-polishing: Can cause relief around pores and layer boundaries

- Frequent cleaning: Clean between polishing steps to prevent compound buildup in pores

- Ultrasonic cleaning: Consider ultrasonic cleaning after final polish to remove trapped polishing compound

- Monitor relief: Check for relief around pores and layer boundaries that may indicate over-polishing

Example Products: Diamond Abrasivessuitable diamond polishing compounds for AM sample preparation

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Polishing PadsPolishing pads and cloths for different polishing stages

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Etching

Etching AM samples reveals the microstructure, layer boundaries, and process defects. The choice of etchant depends on the base material (stainless steel, titanium, nickel alloys, etc.) and the features you want to reveal.

Etchant Selection

Use standard etchants for the base material, but consider:

- Material-specific etchants: Use appropriate etchants for the base alloy (e.g., Vilella's Reagent for stainless steel, Kroll's Reagent for titanium)

- Electrolytic etching: May provide better control for revealing layer boundaries and fine microstructural features

- Multiple etchants: Different etchants may reveal different features, so consider using multiple etchants on different samples or re-polishing and re-etching

Etching Procedure

- Ensure sample is clean and dry

- Apply etchant with cotton swab or immerse sample

- Etch for appropriate time (may need to adjust from standard times due to microstructural differences)

- Immediately rinse with water, then alcohol

- Dry with compressed air

- Inspect under microscope and re-etch if necessary

Special Considerations

- Layer boundaries: May etch differently than bulk material, creating contrast

- Pores: May trap etchant, requiring thorough rinsing

- Anisotropic response: Different orientations may etch at different rates

- Over-etching: Can obscure fine features, so start with shorter times

Etching solutions and reagents for AM materials. Use material-specific etchants based on the base alloy (stainless steel, titanium, nickel alloys, etc.).

Example Products: EtchantsEtching solutions and reagents for AM materials

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Revealing Build Direction and Layer Interfaces

One of the most important aspects of AM sample preparation is revealing the build direction and layer interfaces. This requires careful sectioning orientation and appropriate etching.

Sectioning for Build Direction

To reveal build direction (Z-axis):

- Section perpendicular to the build plate (parallel to build direction)

- This reveals layer boundaries, columnar grain growth, and vertical porosity distribution

- Allows analysis of layer-to-layer bonding and fusion quality

Sectioning for Layer Planes

To reveal layer plane microstructure (XY plane):

- Section parallel to the build plate (perpendicular to build direction)

- This reveals in-plane grain morphology and defect distribution

- Shows the microstructure within individual layers

Revealing Layer Boundaries

Layer boundaries may be revealed through:

- Microstructural differences: Different grain sizes or phase distributions at layer boundaries

- Oxide films: Thin oxide layers that etch differently

- Porosity: Pores concentrated at layer boundaries

- Etching contrast: Different etching response due to microstructural variations

Documentation

Always document the sectioning orientation relative to the build direction:

- Mark the build direction on the sample or mount

- Include orientation information in your notes and images

- Use consistent terminology (e.g., "Z-axis section" or "XY plane section")

Cast titanium microstructure showing directional solidification patterns similar to those observed in AM materials. The columnar grain growth and layer-like structures demonstrate the importance of proper sectioning orientation to reveal build direction.

Process Defect Analysis

AM processes can introduce various defects that must be preserved and revealed during sample preparation. Understanding these defects is critical for process optimization and quality control.

Common AM Defects

Porosity Defects

- Lack-of-fusion pores: Irregularly shaped, often at layer boundaries, from insufficient energy input

- Gas pores: Spherical, from trapped gas in powder or atmosphere

- Keyhole pores: Elongated, from excessive energy input causing keyhole collapse

Microstructural Defects

- Incomplete fusion: Lack of bonding between layers

- Grain boundary defects: Abnormal grain growth or boundary migration

- Phase segregation: Non-uniform phase distribution

- Residual stress: May cause microcracking or distortion

Geometric Defects

- Layer misalignment: Shifts between layers

- Surface roughness: From incomplete fusion or support structures

- Dimensional inaccuracy: From thermal distortion or process parameters

Preparation for Defect Analysis

To properly reveal and analyze defects:

- Use careful sectioning to preserve defect locations

- Avoid smearing or filling defects during grinding and polishing

- Use appropriate etchants to reveal defect boundaries

- Consider using multiple sectioning planes to fully characterize defects

- Document defect locations relative to build direction and layer number

Troubleshooting

Common Issues and Solutions

Pores Filled with Polishing Compound

- Problem: Polishing compound trapped in pores

- Solution: Use ultrasonic cleaning after polishing, reduce polishing time, or use less aggressive polishing compounds

Layer Boundaries Not Visible

- Problem: Layer boundaries not revealed after etching

- Solution: Try different etchants, adjust etching time, or check sectioningorientation (may need to section perpendicular to layers)

Smearing in Porous Regions

- Problem: Material smeared over pores during grinding or polishing

- Solution: Reduce pressure, use sharper abrasives, or increase cleaning frequency

Relief Around Pores

- Problem: Excessive relief making pores appear larger than they are

- Solution: Reduce polishing time, use harder polishing cloths, or adjust polishing pressure

Poor Edge Retention

- Problem: Porous edges rounding or losing definition

- Solution: Use harder mounting materials, reduce polishing time at edges, or use edge retention techniques

Anisotropic Polishing

- Problem: Different regions polishing at different rates

- Solution: This is normal for AM materials; adjust polishing time to ensure all regions are properly polished, or use longer polishing times

Explore More Procedures

Browse our comprehensive procedure guides for material-specific preparation methods and get personalized recommendations.