Composites Preparation

A comprehensive guide to preparing composite material samples for metallographic analysis, covering specialized techniques to avoid fiber pullout, maintain fiber orientation, and reveal matrix-fiber interfaces.

Introduction

Composite materials, including fiber-reinforced composites (FRCs), present unique challenges in metallographic preparation. These materials consist of two or more distinct phases, typically a matrix material (polymer, metal, or ceramic) reinforced with fibers (carbon, glass, aramid, or ceramic). The heterogeneous nature of composites requires specialized techniques to preserve the integrity of both phases and reveal the true microstructure.

Polymer-graphite composite, 200X magnification. This image demonstrates proper composite preparation with intact fibers, clear matrix-fiber interfaces, and minimal pullout artifacts.

Key Challenge: Composites are particularly susceptible to fiber pullout, delamination, and interface damage during preparation. The matrix and fiber phases often have vastly different mechanical properties, making uniform preparation difficult. Careful attention to each step is essential to maintain fiber orientation and reveal matrix-fiber interfaces.

Common composite types include carbon fiber reinforced polymers (CFRP), glass fiber reinforced polymers (GFRP), metal matrix composites (MMC), and ceramic matrix composites (CMC). Each type requires specific considerations, but the fundamental principles of careful sectioning, appropriate mounting, gentle grinding, and careful polishing apply to all.

The goal of composite preparation is to achieve a flat, scratch-free surface that preserves the original structure, maintains fiber orientation, reveals the matrix-fiber interface, and allows for accurate microstructural analysis. Unlike monolithic materials, composites often rely more heavily on contrast from polishing rather than etching to reveal structure. The difference in hardness between matrix and fiber phases creates natural contrast when polished correctly, with softer matrices polishing faster than harder fibers, creating slight relief that enhances visibility under the microscope.

Composite Material Characteristics

- • CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer): Very hard carbon fibers in polymer matrix, requires careful handling to prevent fiber pullout

- • GFRP (Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer): Glass fibers in polymer matrix, sensitive to thermal damage during sectioning

- • MMC (Metal Matrix Composites): Ceramic or carbon fibers in metal matrix, may allow some etching of matrix phase. Common examples include aluminum matrix composites and titanium matrix composites

- • CMC (Ceramic Matrix Composites): Fibers in ceramic matrix, very hard, requires diamond abrasives throughout

Sectioning

Sectioning composite materials requires careful consideration of the matrix and fiber properties. The goal is to minimize damage to both phases and avoid delamination or fiber pullout. Cutting parameters must be optimized to prevent excessive heat generation, which can damage polymer matrices or cause thermal degradation.

Cutting Parameters

- Cutting Speed: Slow speeds (100-200 RPM) to minimize heat and mechanical damage. For polymer matrix composites, use 100-150 RPM; for metal matrix composites, 150-200 RPM may be acceptable

- Blade Selection: MAX-E series thin abrasive cut-off wheels (0.5-1.0 mm) for most composites, or diamond blades for very hard ceramic reinforcements

- Cooling: Continuous cooling with water or cutting fluid is essential. Use adequate flow rate to prevent thermal damage to polymer matrices

- Feed Rate: Slow, steady feed (0.5-1.0 mm/min) to avoid excessive pressure and delamination

- Cutting Direction: Consider fiber orientation - cut perpendicular to fiber direction when possible to minimize pullout

Composite-Specific Sectioning Considerations

By Composite Type

- CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer): Use MAX-E blades at 100-120 RPM. Carbon fibers are very hard and can cause blade wear. Monitor blade condition and replace when cutting efficiency decreases. Use continuous water cooling.

- GFRP (Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer): Use MAX-E blades at 100-150 RPM. Glass fibers are brittle and can shatter if cut too aggressively. Very sensitive to heat - ensure adequate cooling throughout the cut.

- MMC (Metal Matrix Composites): Use MAX-E or diamond blades depending on reinforcement hardness. Aluminum matrix composites: 150-180 RPM. Steel matrix: 120-150 RPM. Diamond blades recommended for SiC or B4C reinforcements.

- CMC (Ceramic Matrix Composites): Use diamond blades exclusively. Cutting speed 100-150 RPM. These materials are very hard and abrasive - diamond blades are essential for clean cuts.

Best Practices

- Use thin blades (0.5-1.0 mm) to minimize kerf loss and reduce heat generation

- Maintain constant cooling throughout the cut to prevent matrix damage - flow rate should be sufficient to keep the cut area flooded

- Avoid excessive pressure - let the blade do the work. Excessive force can cause delamination or fiber damage

- For polymer matrix composites, use lower cutting speeds (100-150 RPM) to prevent melting or thermal degradation

- For metal matrix composites with very hard reinforcements (SiC, B4C), consider using diamond blades

- Support the sample properly to prevent flexing and delamination - use appropriate fixtures or clamps

- Consider the fiber orientation when planning the cut direction - cutting perpendicular to fiber direction minimizes pullout

- Mark the fiber orientation on the sample before cutting if it's not obvious, to maintain reference during preparation

Important: Polymer matrix composites are particularly sensitive to heat. Excessive cutting speed or insufficient cooling can cause matrix melting, fiber damage, or interface degradation. Always use adequate cooling and monitor the cutting process carefully.

Example Products: MAX-E Abrasive Cut-Off BladesMAX-E series thin abrasive blades (0.5-1.0 mm) specifically designed for cutting composite materials with minimal heat generation and delamination

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Diamond Cut-Off BladesDiamond blades for cutting hard ceramic matrix composites or metal matrix composites with very hard reinforcements

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Cutting FluidsWater-based cutting fluids for continuous cooling during composite sectioning to prevent thermal damage

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Mounting

Mounting composite samples requires special consideration to preserve the structure and prevent damage to the matrix-fiber interface. The mounting material must provide adequate support without causing thermal damage or chemical interaction with the composite constituents.

Mounting Considerations

- Temperature Sensitivity: Polymer matrix composites require low-temperature mounting to avoid matrix damage

- Pressure Control: Use moderate pressure to avoid crushing or delamination

- Edge Retention: Ensure good edge retention to preserve fiber ends and interfaces

- Chemical Compatibility: Avoid mounting materials that may react with composite constituents

Compression Mounting

For metal matrix composites and some ceramic matrix composites, compression mounting with epoxy resins is preferred due to lower curing temperatures compared to phenolic. Epoxy resins cure at 150-180°C, which is generally safe for metal matrices but may still damage some polymer matrices. Phenolic resins should be avoided for polymer matrix composites due to higher curing temperatures.

- Clean the sample thoroughly to remove cutting fluid and debris

- Place sample in mounting press with epoxy resin (e.g., EpoMet or equivalent)

- Apply moderate pressure: 2000-3000 psi for epoxy (lower than typical metal mounting)

- Heat to 150-180°C and hold for 5-8 minutes

- Cool slowly to room temperature under pressure to minimize thermal stress

Cold Mounting

Cold mounting is strongly recommended for polymer matrix composites (CFRP, GFRP) to completely avoid thermal exposure. This method is essential for temperature-sensitive materials and eliminates the risk of matrix degradation, fiber-matrix interface damage, or delamination from thermal cycling.

- Clean and dry the sample thoroughly - ensure no cutting fluid remains

- Place in mounting cup with two-part epoxy resin (e.g., EpoMet F or equivalent)

- Mix resin and hardener according to manufacturer instructions

- Pour into mounting cup, ensuring sample is properly positioned

- Allow to cure at room temperature (typically 4-8 hours, or overnight for best results)

- Cold mounting eliminates risk of thermal damage to polymer matrices and interfaces

Special Consideration: For composites with soft matrices, use mounting materials with similar hardness to prevent relief during polishing. Vacuum impregnation may be necessary for porous composites or those with internal voids to ensure complete infiltration and support. For composites with high fiber volume fractions, consider using mounting materials with good edge retention properties.

Example Products: Cold Mounting Epoxy ResinsTwo-part epoxy resins for cold mounting polymer matrix composites without thermal damage

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Compression Mounting EquipmentMounting presses with temperature control for metal and ceramic matrix composites

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Grinding

Grinding composite materials requires careful attention to prevent fiber pullout and maintain fiber orientation. The heterogeneous nature of composites means that grinding must be gentle enough to avoid damaging the softer phase (usually the matrix) while still effectively removing sectioning damage.

Grinding Sequence

- 120 grit: Remove sectioning damage (30-60 seconds per step) - use very light pressure

- 240 grit: Remove previous scratches (30-60 seconds)

- 400 grit: Further refinement (30-60 seconds)

- 600 grit: Final grinding step (30-60 seconds)

- 800 grit: Optional for composites requiring finer surfaces (20-40 seconds)

Grinding Parameters

- Pressure: Very light pressure (1-3 lbs per sample) to prevent fiber pullout

- Rotation: Rotate sample 90° between each grit to ensure complete scratch removal

- Water Flow: Continuous water flow to remove debris and prevent loading

- Speed: 240-300 RPM for grinding wheels

- Time: Shorter times per step compared to metals - monitor frequently

Grinding Tips for Composites

- • Use very light pressure throughout - composites are more sensitive than metals

- • Monitor the surface frequently to detect fiber pullout early

- • Use fresh grinding papers - loaded papers can cause excessive pullout

- • For soft matrix composites, consider starting with finer grits (240 or 400)

- • Ensure all scratches from previous grit are removed before proceeding

- • Avoid excessive grinding time which can cause relief between matrix and fiber

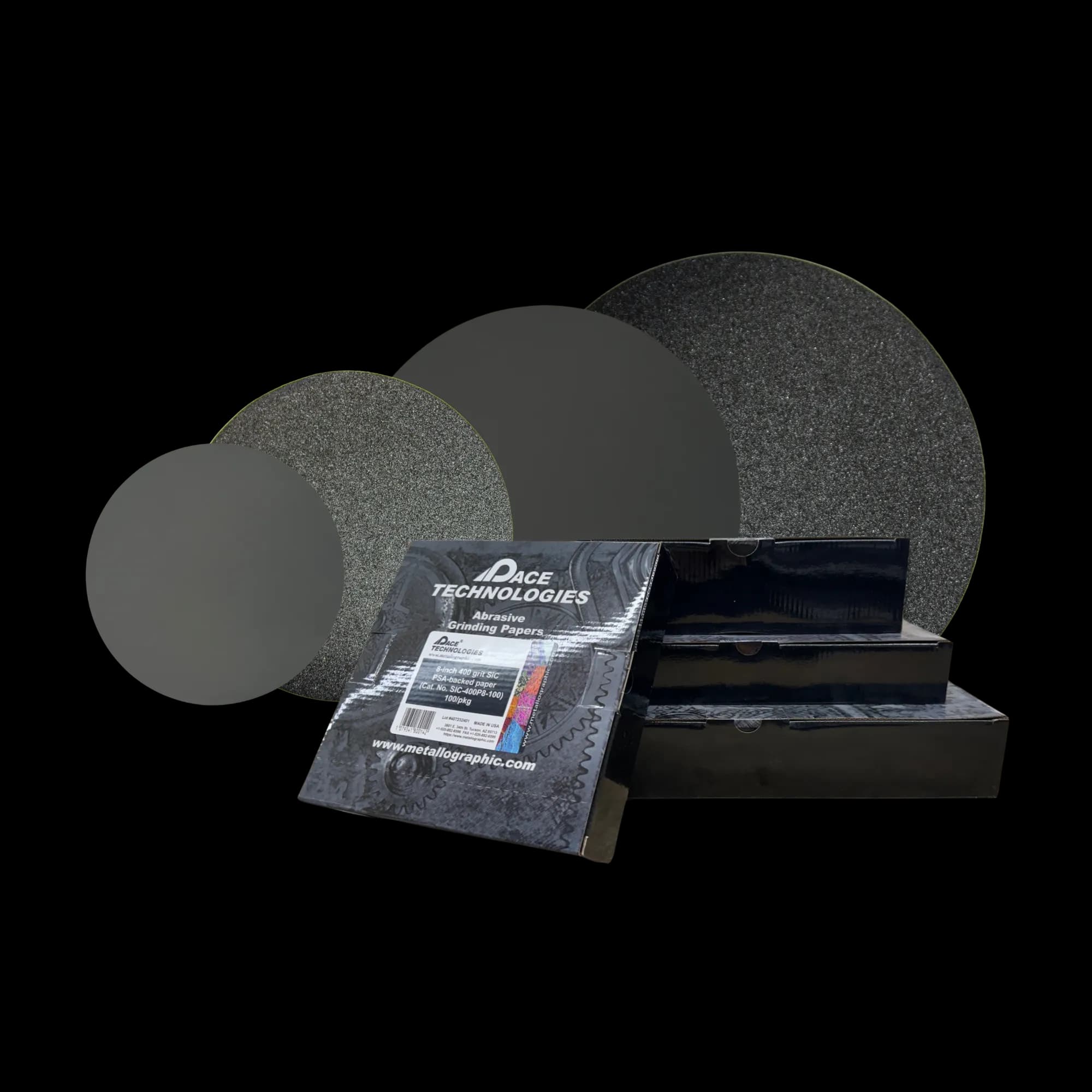

Example Products: Silicon Carbide Grinding Papersappropriate SiC papers in all grit sizes for consistent grinding of composite materials

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Polishing

Polishing is perhaps the most critical step in composite preparation. Careful polishing is essential to avoid fiber damage, prevent pullout, and reveal the matrix-fiber interface. The goal is to achieve a flat surface with good contrast between phases, often relying on polishing-induced contrast rather than etching.

Diamond Polishing Sequence

Use polycrystalline diamond suspensions for consistent cutting action. The sequence below is optimized to minimize fiber pullout while achieving a flat, scratch-free surface.

- 9 μm diamond: 2-4 minutes on a soft cloth (e.g., Microcloth, Texmet 1000, or equivalent soft pad). Use polycrystalline diamond for better cutting consistency

- 3 μm diamond: 2-4 minutes on a soft cloth (Microcloth or equivalent). Monitor for fiber pullout - if observed, reduce pressure

- 1 μm diamond: 2-3 minutes on a soft cloth. This step is critical for removing fine scratches while preserving fiber integrity

- 0.25 μm diamond: Optional - 1-2 minutes on a very soft cloth (e.g., Microcloth or Chemomet). Only use if needed for very fine surfaces

Final Polishing

Final polishing with colloidal silica creates the natural contrast between matrix and fiber phases that is essential for composite microstructural analysis.

- 0.05 μm colloidal silica: 30-90 seconds on a very soft cloth (Microcloth or Chemomet). Use minimal pressure (1-2 lbs)

- Rinse thoroughly with water and dry with compressed air - avoid wiping which can cause fiber pullout

- For composites, final polish often provides sufficient contrast without etching. The differential polishing rates of matrix and fiber create natural contrast

Polishing Parameters

- Pressure: Very light pressure (1-3 lbs per sample) - critical to prevent fiber pullout. Use the minimum pressure that maintains contact

- Speed: 120-150 RPM for diamond polishing. Lower speeds (100-120 RPM) may be beneficial for very sensitive composites

- Cloth Selection: Use soft cloths throughout (Microcloth, Texmet 1000, or equivalent). Avoid hard cloths which can cause excessive pullout

- Lubricant: Polycrystalline diamond suspension in water-based lubricant. High-viscosity suspensions help maintain diamond particles in contact with the surface

- Direction: Consider fiber orientation - polish perpendicular to fiber direction when possible. For random fiber orientations, use gentle circular motions

- Time: Monitor frequently. Shorter times per step are often better than extended polishing which can cause relief

Critical Consideration: Fiber pullout is the most common problem in composite polishing. Use very light pressure, soft cloths, and monitor the surface frequently. If pullout occurs, return to a previous polishing step and use even lighter pressure. The matrix-fiber interface must be preserved to reveal the true microstructure.

Maintaining Fiber Orientation

Throughout the polishing process, maintain awareness of fiber orientation. Polishing parallel to fiber direction can cause excessive pullout, while polishing perpendicular to fibers helps maintain interface integrity. For random fiber orientations, use gentle, circular motions with very light pressure.

Example Products: Polycrystalline Diamond AbrasivesHigh-viscosity polycrystalline diamond suspensions (9 μm, 3 μm, 1 μm, 0.25 μm) for consistent cutting action in composite preparation

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Soft Polishing ClothsSoft polishing pads and cloths (Microcloth, Texmet 1000, Chemomet) designed to minimize fiber pullout in composite materials

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Example Products: Colloidal Silica0.05 μm colloidal silica for final polishing to create natural contrast between matrix and fiber phases

For purchasing options and product specifications, see commercial supplier website.

Etching

Etching options for composite materials are often limited, especially for polymer matrix composites. Many composites rely primarily on contrast achieved through careful polishing rather than chemical etching. However, some etching may be beneficial for metal matrix composites or for revealing specific features.

Important Note: Many composite materials, especially polymer matrix composites, do not respond well to traditional metallographic etchants. The contrast between matrix and fiber phases is often best achieved through careful polishing that creates natural contrast from the different hardnesses of the phases.

Etching Considerations

- Polymer Matrix Composites: Generally not etched - rely on polishing contrast. This applies to CFRP and GFRP materials

- Metal Matrix Composites: May benefit from standard metal etchants applied to the matrix. Aluminum matrix composites can be etched with Keller's reagent, while titanium matrix composites may respond to Kroll's reagent

- Ceramic Matrix Composites: Limited etching options - often rely on polishing contrast

- Interface Revelation: Polishing-induced contrast often reveals interfaces better than etching

Polishing-Induced Contrast

For most composites, the best contrast is achieved through careful polishing rather than etching. The different hardnesses of the matrix and fiber phases create natural contrast when polished properly. Soft matrices polish faster than hard fibers, creating slight relief that enhances visibility under the microscope. This relief is typically on the order of 0.1-0.5 μm, which is sufficient for good contrast under brightfield illumination and excellent contrast under differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

Polymer-graphite composite, as-polished (no etching), 200X magnification. This image demonstrates excellent contrast achieved through careful polishing alone, with clear distinction between matrix and fiber phases.

Limited Etching Options

When etching is attempted for metal matrix composites, use standard etchants for the matrix material (e.g., Keller's reagent for aluminum matrix composites, Nital for steel matrix). However, etching times should be reduced, and the process should be monitored carefully to avoid over-etching the matrix or damaging the fiber-matrix interface.

Etching Procedure (if applicable)

- Ensure sample is clean and dry before etching

- Apply etchant sparingly using cotton swab (for metal matrix composites only)

- Etch for shorter times than for monolithic materials (5-15 seconds)

- Monitor etching progress carefully

- Rinse immediately with water, then alcohol

- Dry with compressed air

Best Practice

For most composite materials, focus on achieving excellent polishing quality rather than relying on etching. The natural contrast from polishing often provides better results than attempting to etch heterogeneous materials. Use differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to enhance contrast if available.

Troubleshooting

Common Issues and Solutions

Problem: Fiber Pullout

Symptoms: Holes or gaps where fibers should be, missing fiber ends, disrupted fiber orientation, visible voids in the microstructure

Root Causes: Excessive polishing pressure, use of hard polishing cloths, insufficient grit progression, polishing parallel to fiber direction, over-polishing

Solutions: Reduce polishing pressure significantly (1-2 lbs per sample), use softer polishing cloths (Microcloth, Texmet 1000), extend polishing times at each step with lighter pressure, ensure proper grit progression (don't skip grits), consider vibratory polishing for final steps, polish perpendicular to fiber direction when possible, use polycrystalline diamond for more consistent cutting action, monitor surface frequently with low-power microscopy to detect pullout early

Problem: Loss of Fiber Orientation

Symptoms: Fibers appear misaligned, original orientation not preserved

Solutions: Use lighter pressure during all steps, avoid excessive grinding/polishing, maintain consistent sample orientation, mark fiber direction before sectioning, use slower cutting speeds during sectioning

Problem: Poor Interface Revelation

Symptoms: Matrix-fiber interface not visible, unclear boundaries between phases

Solutions: Improve polishing quality, use final polish with colloidal silica, ensure flat surface (no relief), use differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, adjust lighting conditions, ensure proper contrast from polishing

Problem: Soft Matrix Damage

Symptoms: Excessive relief around fibers, smearing of matrix material, distorted matrix structure

Solutions: Use very light pressure, softer polishing cloths, shorter polishing times, start with finer grits if matrix is very soft, use mounting material with similar hardness to matrix

Problem: Delamination

Symptoms: Separation of layers, gaps between plies, visible delamination cracks

Solutions: Reduce cutting speed during sectioning, use adequate cooling, support sample properly during cutting, use vacuum impregnation during mounting if necessary, avoid excessive pressure during mounting

Problem: Insufficient Contrast

Symptoms: Matrix and fiber phases difficult to distinguish, poor visibility of interfaces, uniform appearance under brightfield illumination

Root Causes: Over-polishing (too much relief removed), insufficient final polish, matrix and fiber have similar hardness, improper polishing technique

Solutions: Improve final polishing quality with 0.05 μm colloidal silica on very soft cloth, use DIC (differential interference contrast) microscopy to enhance contrast, adjust lighting conditions (try oblique illumination), ensure proper surface flatness (no excessive relief), consider using polarized light for certain fiber types (glass fibers), verify polishing has created natural contrast between phases, reduce final polish time if over-polishing has occurred, ensure proper grit progression was followed

Problem: Thermal Damage

Symptoms: Melted or degraded matrix, discoloration, interface damage

Solutions: Use cold mounting instead of compression mounting, reduce cutting speed, increase cooling during sectioning, use lower mounting temperatures, avoid excessive heat during any preparation step

Explore More Procedures

Browse our comprehensive procedure guides for material-specific preparation methods and get personalized recommendations.