History of Metallography

Explore the evolution of metallography from its origins to modern techniques. Understand how the field has developed over time and the key innovations that shaped metallographic analysis.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Metallography, the study of the microstructure of metals and alloys, has evolved over thousands of years, shaped by human curiosity, industrial needs, and advances in microscopy. From early empirical observations to today's sophisticated analytical techniques, the field has continuously evolved to provide deeper insights into material properties and behavior.

Pearlite and ferrite microstructure - the type of structures that metallography reveals and helps us understand

Understanding the history of metallography helps us appreciate the techniques we use today and provides context for why certain methods became standard practice. This guide traces the key milestones in metallographic development, from ancient metalworking to modern automated analysis systems.

For upcoming metallographers, learning this history provides several important benefits:

- Understanding fundamentals: Historical context helps explain why certain techniques and principles are fundamental to the field

- Appreciating standards: Knowing how standards developed helps understand their importance and proper application

- Recognizing innovation: Understanding past breakthroughs helps identify when new techniques represent genuine advances

- Building expertise: Familiarity with historical figures and their contributions provides a foundation for deeper learning

Ancient Foundations (pre-1800s)

Early civilizations such as the Egyptians, Chinese, and Mesopotamians used metals extensively and developed heat-treating techniques intuitively. Although they did not have microscopes, they recognized that processing affected properties such as hardness, brittleness, and ductility.

Gray iron microstructure - ancient metalworkers worked with similar materials, though they couldn't see these structures

These empirical observations laid the groundwork for later scientific study. Ancient metalworkers learned through trial and error that:

- Heating and cooling rates affected metal properties

- Different metal compositions produced different behaviors

- Mechanical working (forging, hammering) could alter material characteristics

- Quenching in various media produced different results

While these early practitioners lacked the tools to see microstructures, their understanding of the relationship between processing and properties was remarkably sophisticated and formed the foundation for modern metallurgical science.

Birth of Metallography (1800–1860)

The invention of the compound optical microscope in the early 17th century (around 1600) made metal microstructure theoretically visible, but polishing and etching methods were still primitive. The true birth of metallography as a scientific discipline came in the mid-19th century with the pioneering work of Henry Clifton Sorby.

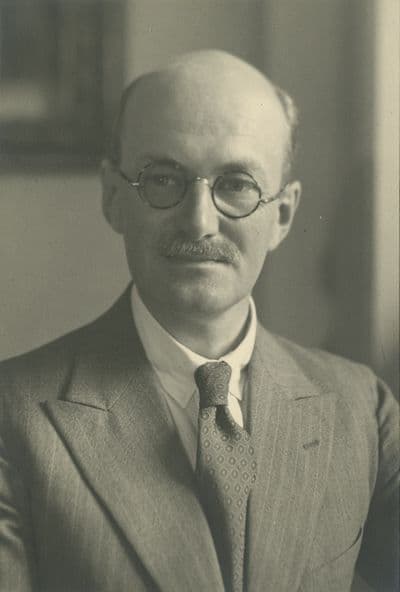

Henry Clifton Sorby: The Father of Metallography

Henry Clifton Sorby (1826–1908), considered the "Father of Metallography"

Henry Clifton Sorby (1826–1908) is universally recognized as the "Father of Metallography." In 1863, Sorby adapted techniques from petrography (the study of rocks) to examine metals, developing reliable mechanical polishing and chemical etching techniques that revolutionized the field.

Key Achievement: Sorby published the first micrographs showing pearlite, ferrite, and other structures in steel. His work proved that microstructure governs mechanical properties, establishing the fundamental principle that still guides metallographic analysis today.

Sorby's contributions included:

- Development of systematic sample preparation methods (grinding and polishing)

- Creation of techniques for examining metal specimens under reflected light microscopy

- First detailed observations and documentation of steel microstructures (pearlite, ferrite)

- Establishment of the connection between microstructure and mechanical properties

- Adaptation of petrographic techniques to metallurgical applications

His techniques laid the foundation for all modern metallographic practices, and the fundamental principles he established remain relevant today. Sorby's work demonstrated that the internal structure of metals could be systematically studied and understood, transforming metallurgy from an empirical craft into a scientific discipline.

Industrial Revolution & Scientific Expansion (1860–1930)

The rapid development of steelmaking processes (Bessemer, Siemens-Martin) during the Industrial Revolution increased demand for metallurgical science and drove significant advances in metallography.

Key Researchers and Contributions

Following Sorby's foundational work, several researchers made critical contributions that refined understanding of phase transformations in metals and established the theoretical framework for modern metallography:

- Dmitry Konstantinovich Chernov (1839–1921) - A Russian metallurgist who discovered polymorphic transformations in steel and developed the iron-carbon phase diagram, marking a crucial advancement in scientific metallography. His work on critical temperatures (now known as A1, A3, and Acm points) was foundational.

- Floris Osmond (1849–1912) - A French scientist who named several phases in iron and steel microstructures, including martensite (after Adolf Martens) and cementite. He introduced the Greek letter symbols (α, β, γ, δ) for steel phases that are still used today.

- Henry Marion Howe (1848–1922) - An American metallurgist and the first president of ASTM. Howe made significant contributions to understanding steel microstructures and heat treatment, and was instrumental in establishing metallography as an academic discipline.

- Edgar C. Bain (1891–1971) - An American metallurgist who discoveredbainite, a microstructure formed at intermediate transformation temperatures. His work on isothermal transformation diagrams (TTT curves) was groundbreaking.

- Albert Sauveur (1863–1939) - A Belgian-American metallurgist who established the first metallography laboratory at Harvard University. He improved microphotography techniques for metals, analyzed various alloy constituents, and helped establish international nomenclature for microstructural features.

- Emil Heyn (1867–1922) - A German metallurgist who introduced quantitative metallography. He developed the intercept method for grain size measurement, which remains a standard technique today (ASTM E112).

These researchers' work helped explain how different heat treatments, cooling rates, and compositions produced different microstructures and properties, establishing the scientific basis for modern materials engineering.

Phase Diagrams and Predictive Power

William Hume-Rothery (1899–1968), key contributor to metallurgical phase diagrams and alloy theory

The development of metallurgical phase diagrams, building on Chernov's iron-carbon diagram, provided predictive power that transformed metallography from descriptive to predictive science. Key contributors included William Hume-Rothery (1899–1968), who developed the Hume-Rothery rules for predicting solid solution formation in alloys, and Léon Guillet (1873–1946), a French metallurgist who contributed to understanding aluminum alloys and phase relationships. These diagrams allowed metallographers to:

- Predict phase formation at different temperatures and compositions

- Understand equilibrium and non-equilibrium transformations

- Design heat treatments to achieve desired microstructures

- Explain the relationship between composition, processing, and properties

- Understand solid solution formation and intermetallic compound stability

Documentation and Teaching

The introduction of photomicrography allowed documentation and teaching of microstructures. This development was crucial for:

- Sharing knowledge across laboratories and countries

- Creating reference collections of microstructures

- Teaching metallography to new generations

- Standardizing terminology and classification

Example microstructure showing ferrite and pearlite in steel - the type of structures that early metallographers like Sorby first documented

Standardization and ASTM Committee E-4

The need for standardized methods led to the formation of ASTM Committee E-4 on Metallographyin 1916 (initially as "Committee E-4 on Magnification Scales for Micrographs," renamed in 1920). This committee, organized by Edgar Marburg with founding members including Dr. Henry Marion Howe(first ASTM president) and George Kimball Burgess (Director of the National Bureau of Standards), began developing standards that would shape the field. The first standard, E 2 (Methods for Preparation of Micrographs of Metals and Alloys), was introduced in 1917, establishing foundational practices that continue to guide metallography today.

By the end of this period, metallography had become an established scientific discipline with standardized methods, theoretical foundations, and practical applications in industry.

Electron Microscopy Era (1930–1970)

The development of the transmission electron microscope (TEM) and later the scanning electron microscope (SEM) revolutionized metallography, enabling observation of structures at previously unimaginable scales.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

- 1931: First TEM developed by Ernst Ruska andMax Knoll

- 1940s-1950s: TEM became commercially available, enabling observation of dislocations, fine precipitates, and nanoscale structures

- Scientists could now see defects and microstructural features that were impossible to observe with optical microscopes

SEM image at 20,000X magnification - demonstrating the resolution capabilities that electron microscopy brought to metallography

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

- 1937: First SEM concept developed by Manfred von Ardenne

- 1942: Vladimir Zworykin and colleagues at RCA developed a practical SEM design

- 1965: First commercial SEM introduced by Cambridge Scientific Instruments (Cambridge Stereoscan), providing three-dimensional imaging capabilities

- SEM offered superior depth of field compared to optical microscopes (up to 100x greater)

- Enabled detailed examination of fracture surfaces, complex microstructures, and surface topography at high magnifications

- Combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), SEM allowed simultaneous imaging and chemical analysis

Impact on Industry

Metallography became essential for aerospace, automotive, nuclear, and defense industries. The ability to see dislocations, grain boundaries, and nanoscale defects transformed:

- Materials development and optimization

- Failure analysis and quality control

- Understanding of material behavior under various conditions

- Design of new alloys and heat treatments

These developments allowed metallographers to study materials at the nanoscale, revealing structures and defects that fundamentally changed our understanding of material behavior.

Digital and Analytical Metallography (1970–Present)

The latter half of the 20th century and early 21st century brought significant advances in automation, digital imaging, and analytical techniques. Major advancements include:

Computer-Aided Analysis

- Computer-aided image analysis and automated grain size measurement

- Digital cameras replacing film photography (1980s)

- Image analysis software for automated phase quantification (1990s)

- High-resolution digital imaging systems with improved dynamic range (2000s)

Modern digital imaging enables precise microstructure documentation

Differential interference contrast (DIC) provides enhanced detail

Advanced Analytical Techniques

- EBSD (Electron Backscatter Diffraction) for crystallographic mapping

- EDS/WDS microanalysis, combining chemistry with microstructure

- High-resolution SEM and FIB (Focused Ion Beam) for 3D microstructural reconstruction

- Automated hardness mapping and micro-mechanical testing

- X-ray Computed Tomography for non-destructive 3D imaging

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for surface topography at nanometer resolution

Automation and Standardization

- 1943: Electrolytic polishing introduced by Struers (Micropol), providing an alternative to mechanical polishing for certain materials

- Automated grinding and polishing equipment (1960s-1970s), reducing operator variability

- Standardized preparation procedures for different material classes (1980s), ensuring reproducibility across laboratories

- Computer-controlled preparation systems with programmable parameters (1990s), allowing precise control of force, speed, and timing

- Advanced mounting materials and techniques for challenging samples (2000s), including conductive mounts and vacuum impregnation

- Machine learning and artificial intelligence for automated microstructure classification and defect detection (2010s-present)

- Development of international standards (ASTM, ISO) for sample preparation, testing, and reporting, ensuring consistency and quality

Current State

Today, metallography is a cornerstone of materials engineering, failure analysis, quality control, and research. Modern laboratories combine traditional techniques with cutting-edge technology to provide comprehensive material characterization.

The Enduring Value of Fundamentals

Despite all the technological advances, the fundamental principles established by early metallographers like Sorby remain relevant today. Proper sample preparation, careful observation, and systematic analysis are as important now as they were over a century ago. Modern technology enhances our capabilities, but it doesn't replace the need for understanding the basics of metallographic practice.

Understanding this history helps metallographers appreciate why certain techniques became standard practice, recognize the importance of proper sample preparation, and understand the scientific principles underlying modern methods. The work of pioneers like Sorby, Chernov, Osmond, and others established the foundation upon which all modern metallography is built.

Recommended Resources to Learn Metallography

Below are the best options depending on your preferred learning style. These resources provide comprehensive coverage of metallographic principles, techniques, and applications.

Textbooks (Highly Recommended)

📘 ASM Handbook – Volume 9: Metallography and Microstructures

Gold standard reference in the field. Covers preparation, etching, microstructures of all major alloys, digital imaging, SEM/TEM, failures, and more. Ideal for both beginners and professionals.

Visit ASM International →📘 George F. Vander Voort – "Metallography: Principles and Practice"

One of the clearest and most practical textbooks. Extremely thorough preparation guidelines and excellent microstructure images.

Find at ASM International →📘 Samuels – "Metallographic Polishing by Mechanical Methods"

Classic reference on grinding, polishing, and sample preparation. Essential reading for understanding mechanical preparation techniques.

📘 "Practical Metallography" by Petzow

Deep dive into etching, microstructure interpretation, and metal-specific preparation. Excellent for advanced practitioners.

Professional Organizations

ASM International

Courses, webinars, certifications, technical books. Offers live and online classes in metallography and failure analysis.

Visit ASM International →International Metallographic Society (IMS)

Conference proceedings, competitions, and best-practice methods. Good for staying current with modern techniques.

Visit IMS →Online Resources (Free or Low-Cost)

Metallurgical Textbook Archives

Many older (but still valuable) texts are public domain:

- Howe & Campbell – Metallography (early 1900s)

- Osmond – Microscopic Examination of Iron and Steel

Search for these in public domain archives and university libraries.

YouTube Channels

- ASM International

- Materials Science Lecture Series

- University channels (MIT, Georgia Tech, etc.)

Metallography Websites

Leading equipment and consumable suppliers offer excellent guides, videos, and application notes:

Courses (Online Learning)

Coursera / edX

Materials Science courses covering microstructures, phase diagrams, and microscopy. Many courses are free to audit.

ASM Online Metallography Courses

Hands-on advice for sample prep, imaging, and interpretation. Professional-level training with certification options.

View ASM Courses →Getting Started

For beginners, we recommend starting with the ASM Handbook Volume 9 or Vander Voort's textbook, combined with hands-on practice. Supplement your learning with online resources and consider taking a formal course if you're pursuing metallography professionally. The combination of theoretical knowledge and practical experience is essential for mastering metallographic techniques.